Detroit, the City of Champions

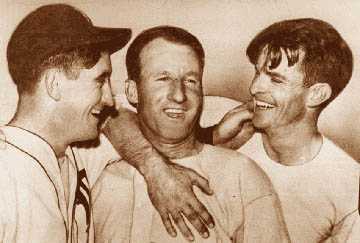

Series celebrate in the clubhouse after the game.

Goose Goslin, center, drove in Mickey Cochrane,

left, with the winning run on a bloop single.

At right is the winning pitcher, Tommy Bridges.

It was the middle of the Great Depression and Detroit was particularly hard hit, with more than 220,000 out of work. Homeowners couldn't pay their mortgages or property taxes, forcing banks to close and bringing on a fiscal crisis in the city. City workers, lucky to have jobs at all, were forced to take pay cuts. The idled Fisher Body Plant reopened as the Fisher Lodge, a shelter for homeless men.

But despite the hardships, it was a time for celebration like no other, a time for Detroit to revel in its newly won reputation as "The City of Champions."

with Joe Louis prior to a game at Navin Field in 1935.

It began when native son Gar Wood and his racing boats won the Harmsworth Trophy for unlimited powerboat racing on the Detroit River in 1931. The following year Eddie "the Midnight Express" Tolan, a black student from Detroit's Cass Technical High School, won the 100- and 200-meter races and two gold medals at the 1932 Olympics.

It continued as Detroit's own "Brown Bomber," Joe Louis, captured national attention on his way to the heavyweight championship of the world, and was bolstered when the Detroit Red Wings won the National Hockey League's Stanley Cup and the Detroit Lions won the National Football League championship in 1935. The Detroit Tigers won the American League pennant in 1934 and again in 1935. And it was the Tigers who made the "City of Champions" title stick by winning the World Series in 1935, defeating the Chicago Cubs.

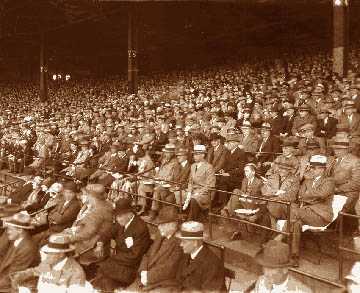

The Depression failed to diminish Americans' love affair with baseball. After all, it was cheap to play, it was fun at any skill level and it required no elaborate playing field or equipment. And it only cost 50 cents to sit in the bleachers at Navin Field and watch the Tigers play.

Fans walked or took the trolley to Michigan and Trumbull and, despite the grim realities of the Depression, began filling the ballpark day after day.

Said Tiger second baseman Charlie Gehringer, "It was a little different than it is today. Everybody dressed like they were going to the theater or maybe church. We played in the afternoons and the lawyers would come out from their offices. They would be all spiffed up. The women in the box seats looked just beautiful. You'd think they were there for a garden party."

it was cheap to play, it was fun at any skill level and

it required no elaborate playing field or equipment.

Attendance soared to 919,191 in 1934 and topped the one-million mark in 1935.

According to some reports, Detroit accounted for more than one-quarter of baseball's total number of paying customers during this period.

And why not? The Tigers' roster consisted of some of the most famous names ever to play the game. Men like Mickey "Black Mike" Cochrane, the bold and brash playing manager; Billy Rogell, the hawk-nosed but graceful shortstop; Leon "Goose" Goslin; "Hammerin'" Hank Greenberg, the gentle giant who owned first base, and Charlie Gehringer, the "Mechanical Man, " so named for his unfailing consistency at second base..

Although the players didn't make the millions that today's stars do, they commanded enviable salaries. But the fans didn't mind. To them they represented hope that times would get better.

Greenberg and Gerhinger became known as "the G--Men of Detroit". Together, they formed an unbeatable pair. Gehringer would get on base and Greenberg would drive him home. Greenberg would tell Charlie, "just get them around to third, and I'll send them in." And send them in, he did.

When the Tigers won the pennant and the World Series in 1935, Greenberg drove in 170 runs with a .313 average.

Lynwood "Schoolboy" Rowe joined the Tigers in 1934 and became one of the most powerful pitchers in the league, running up a 24-8 record. He won 16 games in a row to tie a major league record. But according to The Detroit News' Joe Falls, Rowe specialized in beating the New York Yankees.

Tiger owner Frank Navin acquired veteran outfielder Goose Goslin from the Washington Senators and watched him play a major role in capturing the '34 and '35 pennants. Tommy Bridges had outstanding seasons with Detroit with his wicked curveball.

accounting for nearly 25 percent of baseball's total paid

attendance during the period. It cost a dollar to get into the

grandstands, 50 cents for a bleacher seat.

The Tigers ended the '34 season with six players hitting .300 or better. But they lost the World Series to the Cardinals in one of the wildest championship games ever played.

As the seventh and final game was about to get under way in Detroit, Cardinal pitcher Dizzy Dean taunted the Tigers and their fans by parading in front of the stands with a tiger-skin rug over his shoulders, proclaiming "I've got me a Tiger skin already."

By the sixth inning the Tigers were well behind and the frustrated fans were becoming restless. Cardinal slugger Joe Medwick tripled and knocked down the Tigers' Marv Owen in a vicious slide into third base. The two men pushed and shoved each other before being pulled apart, but when Medwick went out to left field the following inning he was met with a shower of tomatoes, apples, and other missiles.

New York Daily News reporter Paul Gallico described it as the "dizziest, maddest, wildest and most exciting World Series game interrupted by one of the wildest riots ever seen in a ball park."

They lost the World Series that year to the St. Louis Cardinals

after one of the wildest championship games ever.

The debris continued to shower the field faster than the grounds crew could pick it up and Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis, watching the game from a box seat, suspended play and to the astonishment of both teams ordered Medwick to leave the field.

The Cardinals went on to win the game and the World Series that day. The final score was 11-0. But it left a bitter taste in the mouths of fans who stormed the infield and ripped up home plate in their frustration. But they only had to wait a year for the sweet taste of victory.

The 1935 World Series against the Chicago Cubs started badly for the Tigers. In game two, Hank Greenberg collided with Cubs catcher Gabby Hartnett and broke his wrist, sidelining him for the rest of the Series. But other players picked up the slack and on October 7, 1935, Goose Goslin singled into right field, driving home Mickey Cochrane with the winning run, giving the Tigers a 4-3 victory in the sixth game and the World Series.

Delirious fans rushed onto Navin Field in celebration, spilling out onto Michigan Ave. and Trumbull. For a few hours the money worries of the Depression were gone and the only thing that mattered was Detroit, "City of Champions."