Selfridge Field and the beginnings of air power

The mud flats bordering Lake St. Clair near Mt. Clemens have been on the cutting edge of history since the Joy Realty Company of Detroit first developed a crude landing field early in this century. Since then the field, named after Lt. Thomas Etholen Selfridge, has hosted nearly every important figure in aviation history and played a front line role in America's air defenses.

Known at various times as America's No.1 Hornet's Nest, Home of Generals, and Home of the MiG Killers, the field was first leased by the U.S. Army in 1917. Three years later the Army bought 600 soggy acres from Henry Joy for $190,000. The Army used the field to train pilots as Europe was engulfed in war. Horses pulled mowers to keep the grass cut and mud ruled.

the 94th Aero ("Hat in the ring") Squadron.

The squadron was based at Selfridge.

Selfridge became a school for aircraft mechanics and later became the first aerial gunnery school.

The Army named the base after Selfridge, who was the first secretary of its Aeronautical Experiment Association (AEA). Selfridge loved flying and studied everything he could find on the subject. Early on, as a member of the Military Aeronautics Board, he had recommended that the Army purchase dirigibles.

the plane nosedived to earth.

Selfdrige died of a skull fracture later that day.

Selfridge took his first flight in 1907 on Alexander Graham Bell's tetrahedral kite, a strange structure made up of 3,393 winged cells. It took him 168 feet in the air and flew for an amazing seven minutes. He also flew a craft built by a Canadian engineer, F.W.Baldwin, which soared three feet off the gound for about 100 feet.

Selfridge sudied many of the strange new flying inventions and on March 9, 1908, offered his own design. The AEA designated it Aerodrome No.1. Red silk covered the wings, so it became known as the Red Wing. It flew 318 feet, 11 inches, before collapsing to the ground, leaving the pilot slightly bruised. A second flight wrecked it completely, and only the engine could be salvaged.

However Selfridge's design inspired Glenn Curtiss to build the Flying Jenny.

Lt. Selfridge seemed destined to become the nation's leading military aeronautical engineer. But on Sept. 17, 1908, at Ft. Myer, Va., he became the nation's first soldier to die in a plane crash when he flew with Orville Wright.

Wright later described the accident that killed Selfridge in a letter to his brother, Wilbur:

"On the fourth round, everything seemingly working much better and smoother than any former flight, I started on a larger circuit with less abrupt turns.

"It was on the very first slow turn that the trouble began.

"...A hurried glance behind revealed nothing wrong, but I decided to shut off the power and descend as soon as the machine could be faced in a direction where a landing could be made.

"This decision was hardly reached, in fact I suppose it was not over two or three seconds from the time the first taps were heard, until two big thumps, which gave the machine a terrible shaking, showed that something had broken...

"The machine suddenly turned to the right and I immediately shut off the power.

"...Quick as a flash, the machine turned down in front and started straight for the ground. Our course for 50 feet was within a very few degrees of the perpendicular.

"Lt. Selfridge up to this time had not uttered a word, though he took a hasty glance behind when the propeller broke and turned once or twice to look into my face, evidently to see what I thought of the situation.

"But when the machine turned head first for the ground, he exclaimed 'Oh! Oh!' in an almost inaudible voice.

When the craft hit the ground Selfridge was thrown against one of the wooden uprights of the framework and his skull was fractured. He died later that evening. He was 26.

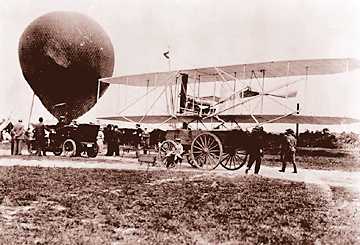

The Army's first airplane is delivered to the Army Air Corps at Fort Myer, Va., in 1909. The plane is being delivered in an Army vehicle under terms of the contract. The Army's first airplane is delivered to the Army Air Corps at Fort Myer, Va., in 1909. The plane is being delivered in an Army vehicle under terms of the contract. |

The army bought its first military airplane in 1909, the year after Selfridge's death.

Oldtimers Carl Smith and B.J. Pollard reminisced in a 1967 News article about the early days at the air base.

"There were no runway lights when it was first built." said Smith. "We used to build fires at the end of the runway to guide planes at night.

Smith and Pollard had both worked at Packard, which had developed the Liberty engine, then the world's largest airplane engine. The Liberty engine was the laughingstock of the country, said Pollard of the 12-cylinder engine which Packard had developed in 1915.

Here Packard had an airplane engine and nothing to fly it in because there wasn't a fuselage in the country big enough to accommodate it. Packard had tested it on a truck. Imagine going out into traffic with a truck propelled by an airplane engine," Pollard said. It became vital to the country to get this engine up in the air--for prestige if nothing else. Just to show people that it could push an airplane.

Selfridge was the only field large enough to accommodate it. I think they made Selfridge just to get that engine off the ground, Pollard said.

The Army imported a DeHaviland fuselage with an 8-cylinder engine, and replaced it with the big Liberty, which fit and worked quite nicely.

Another veteran mechanic, Roy D. Gunn, also recalled the early days at Selfridge. There were a lot of crashes. The pilots would put their planes into dives and sometimes find themselves unable to pull out.

The muddy unpaved field was a problem. When it rained, the landing field became very soft and frequently the small wheels of landing planes would stick in the mud and the planes would nose over.

Winter maneuvers at Selfridge in 1925. Winter maneuvers at Selfridge in 1925. |

In March 1918 a flood drove everyone off the base. The water was above my knees," Gunn said. "I remember that everyone hiked out and over to Mt.Clemens where the soldiers were put up in schools and churches.

Between the flu and flying, we had a lot of funerals," Gunn said.

Selfridge was home to the First Pursuit Group, which produced famed ace Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker. After World War I the unit returned from France to Selfridge where it remained for 20 years, until World War II.

Congress approved funds for improvements at Selfridge, turning it into one of the finest airfields in the nation, the goal of every young pursuit pilot.

In 1922 the base hosted the first John Mitchell Trophy Race. A Selfridge pilot, 1st Lt. D. F. Stace, won with a world speed record of 178 mph. The same year Selfridge pilot 1st Lt. R. Maughn won the Pulitzer Trophy Race and Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell set another record at 224 mph.

In 1924 a lanky young cadet, Charles A. Lindbergh, fresh from San Antonio Air Cadet Training Center, arrived at Selfridge. He returned in 1927 after completing the first trans-Atlantic non-stop solo flight. His Spirit of St. Louis was escorted by a squadron of 22 pursuit planes.

An aerial view of Selfridge Air Base, circa 1930. An aerial view of Selfridge Air Base, circa 1930. |

In 1924 Major Carl A. Spaatz, who became the first chief of staff of the Air Force in 1947, organized and led a spectacular air show at Selfridge, the beginning of a long history of air shows at the base.

In 1925 Selfridge staged a winter war maneuver to see how useful airplanes would be under extreme conditions. A squadron of planes with ice skids flew off to Camp Skeel at Oscoda, Mich. We could carry on this transcontinental campaign into the Arctic regions with the same equipment we have used this week," said squadron commander Maj. Thomas Lamphier.

Later at an Oscoda banquet where the fliers were guests, Lamphier declared his support for Gen. William Billy Mitchell, under fire in Washington for his vigorous promotion of air defenses. Every American officer who wears wings on his uniform is heart and soul behind everything Brig. Gen. Mitchell has told the committees of Congress during the last month.

Mitchell was court-martialed for insubordination and resigned from the army. When his views later proved correct, Congress ordered a Medal of Honor for him.

In 1935 the base joined a top-level network of bases with five others: Mitchell, Langley, Barksdale, March and Hamilton.

During the 1930s and 1940s fliers from Selfridge often performed maneuvers over Detroit, much to the delight of local citizens.

A fighter squadron from Selfridge patrols over Detroit in 1931. A fighter squadron from Selfridge patrols over Detroit in 1931. |

At the outbreak of World War II, the 17th Pursuit Squardon, a longtime Selfridge institution, was rushed to the Philippines. A cadre from Selfridge headed by Col. Lawrence P. Hickey organized the VIII Fighter Command in England, which by the end of the war had 16 fighter groups attacking targets in Europe.

Selfridge kept on turning out new units. It trained the first all-black 332d Fighter squadron, popularly known as The Tuskegee Airmen. Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr., the first black to graduate from West Point in this century, and later the first black Air Force general, led the squadron. A squadron member, Daniel Chappie James, later became the first black to attain the rank of four-star general when he was named Commander of the North American Air Defense Command, (NORAD).

Selfridge also trained hundreds of French airmen during the war.

More than 100 men of the First Pursuit Squardron rose through the ranks to become Air Force generals. Notable among them are Spaatz, Curtis E. LeMay, Frank O'D. Hunter, George H. Brett, James Jimmy Doolittle, Paul B. Wurtsmith, Emmet Rosie O'Donnell and Earle E. Partridge.

In 1947 the base marked its 30th anniversary. The Detroit News carried a five part series on the 56th Fighter Group, which had racked up a total of 1,013 and 1/2 kills during the war in Europe. A rival, the 4th Fighter group, claimed 1,015 kills, but They bagged more on the ground then we did, an officer from the 56th said. The 56th lost a total of 140 aces in two years. But during one month it blasted 72 German planes out of the air with a loss of two.

In 1947 the Air Force separated from the Army, and Selfridge became Selfridge Air Force Base. It continued making innovations and celebrating air history. In 1965 Col. Converse B. Kelly flew a rebuilt Spad World War I biplane as Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker, an ace from that war, watched.

A Selfridge alumnus, Rickenbacker became one of the first American air heros, with 22 enemy kills and four balloon kills, in World War I. Rickenbacker returned in 1967 for Selfridge's 50th anniversary. He noted that his World War I unit, the 94th Hat in the Ring, squadron, had been stationed at Selfridge.

In 1971 Selfridge Air Force Base became Selfridge Air National Guard Base.

It continues making history and now offers displays, memorabilia, artifacts and souveniers in its Selfridge Air Museum headed by H.O. Bedsole (Lt. Col., Ret.) and manned by volunteers including Don Hussey, who contributed to this piece.