And then there were tw

With the Detroit Times gone, the Free Press and News focused exclusively on beating each other. Through the '60s, '70s and '80s, they fought one of America's costliest newspaper wars. As the number of two-paper cities in the country fell, each Detroit newspaper felt that the only way to survive was to dominate in circulation and advertising.

Each spent heavily to do that, discounting papers and ads, selling wherever they could, adding staff and space and foregoing profits today for survival tomorrow.

Under Publisher David Lawrence Jr., now publisher at the Miami Herald, the Free Press launched Operation Tiger -- a plan to win Detroit's newspaper war on every front. Part of the plan was a $22.3 million addition, in 1979, to the riverfront printing plant. When built, it had been the largest offset printing facility in the world.

The battle was not just about money. When armored personnel carriers rolled into Detroit to quell the civil disturbances of 1967, Free Press staffers hitched a ride on one and persuaded Guardsmen to drive over to the News. They demanded a surrender. No way.

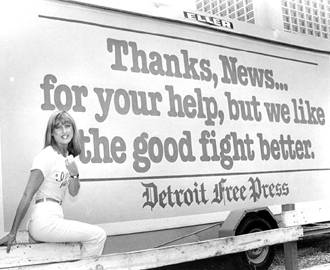

There were occasions when the Free Press and the News found themselves on the same side -- during labor disputes. Unions at the newspapers had banded together for strength, and so did the publishers, who were concerned about being whipsawed, one against the other, with selective strikes. The papers agreed to keep each other's names alive in the event that a strike prevented one or the other from publishing. After a strike, though, it was back to competition as usual. Following a strike in 1980, the Free Press bought a billboard that said, "Thanks, News, for your help, but we like the good fight better."

Despite the fighting words, the first tentative overtures of peace began that year.

The fight was staining each paper's balance sheet with red ink. In the early '80s, each paper operated at a loss. The Free Press had the backing of Knight-Ridder. The News, operated by the family-run Evening News Association, siphoned money from its broadcast operations.

In 1985, the long undervalued price of Evening News Association shares began to soar. The stock was not traded on the open market, so it had been insulated from market forces. In the summer of 1985, its value climbed from $150 a share to $1,000. Some shareholders wanted to get their money out.

The runup pushed Peter Clark, a direct descendent of founder James Scripps, to look for a "white knight" -- a buyer with ideals compatible to News traditions. The knight wore expensive suits and had silver hair. He was Lee Hills' former assistant at the Free Press, Allen Neuharth. Now, he was the top executive at Gannett Co. Inc., America's largest newspaper company.

But there was to be no showdown.

As he explored the Evening News Association, Neuharth revived queries that Knight-Ridder had initiated in 1980 about forming a Joint Operating Agreement. This narrow exception to anti-trust law allows newspapers to combine business operations, if it will save a newspaper that is likely to fail.

Gannett agreed to pay $717 million -- $1,583 a share -- for the Evening News Association.

The Free Press continued to narrow the circulation gap, closing to within 5,000 copies in 1986.

Then, the war was suddenly over, and a new one began.

Knight-Ridder and Gannett announced their application for a JOA. The application tagged the Free Pres as the failing newspaper. Testimony described a downward spiral of financial losses, a second-place share of advertising and declining circulation. Knight-Ridder's directors underscored hearing testimony by saying that, without a JOA, they would close the Free Press -- the nation's 10th largest newspaper -- and ship the presses out of town.

Lawrence, who had once worked tirelessly to defeat the News, worked harder to win the JOA. Part of that effort was quelling opposition, much of it from labor unions that feared losing jobs. Several years later, the JOA and the deal-making that went into clearing union objections were cited as one factor in the longest strike ever against the newspapers. The JOA fight followed a long and torturous path. The first victory was approval by Attorney General Ed Meese, then on his way out of office after a federal investigation. After appeals and reversals, the final word came in a highly unusual tie vote by the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 1989, the Detroit Free Press and News entered into the nation's largest JOA, a 100-year deal to share business operations and split profits as editorial staffs remained competitive.

It would not, however, be an immediate path to stability.