Film

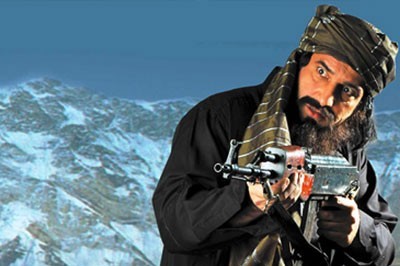

photo courtesy Rahimi International Films

Afghanistan developed a vibrant cinema industry in the 1960s and 1970s despite strong competition from Bollywood. Since 2001 several Afghan productions have attracted international attention.

Historical background

photo courtesy Afghan Film

The first film produced with Afghan participation was Ishq wa Dosti (‘Love and Friendship’, 1946), directed by Rashid Latif in the Huma Film Studios in Lahore and starring Bina and Latif Nashad Malek Khel. This was followed by Qachaq Baran (‘Smugglers’, 1950) and Shab Juma (‘Friday Night’, 1950), both directed by Alil Rawnaq, and Roz Hai Doshwar (‘Difficult Days’, 1952), directed by Wali Latifi.

During the late 1950s Indian films began to dominate the commercial cinema market in Afghanistan. Among the first films to make an impact in Afghanistan was Tapan Sinha's Kabuliwallah ('The Man from Kabul', 1956) which told the story of an Afghan dry fruit seller working in India to make money to take care of his daughter.

Soon after, against a background of growing nationalism, local filmmakers emerged to produce films which identified Afghanistan as an independent nation. Afghanistan’s first home-grown feature film, Rabi’a Balkhi, was made in 1965 by Daoud Farani and A K Halil. A major box office success, it took as its subject matter the life and times of the eponymous 10th-century princess and poetess from Balkh.

In 1968, Afghan Film was founded with US support, and producing documentaries and news films which, in the absence of television, were shown in cinemas. In time, Afghan Film began producing feature films and acquired its own film laboratory and set up the National Film Archives. Despite the absence of formal training in the country for Afghan film-makers, several private studios appeared in wake of Afghan Film, including Nazir Films, Shafaq Films and Ariana Film.

Successful Afghan movies made during the 1960s and 1970s included Manand Oqab (‘Like Eagles’, 1969), directed by Khair Zada and starring Zahir Waida and a young girl named Najia, and Mujasema Hamikhandand (‘The Sculptures are Laughing’, 1975), directed by Abdul Latif. Leading actors of the period included Khan Aga Sarvar, Rafig Seddig, Aziz alla Hadaf, Mashal Honar and Parvin Sanatgar. Hollywood came briefly to Afghanistan in 1971 with the shooting of John Frankenheimer's The Horsemen (USA, 1971).

Meanwhile Afghanistan continued to be an important overseas market for Indian films. One of the biggest blockbusters of the 1970s in Afghanistan was Prakash Mehra’s 1973 film Zanjeer ('Chain'), which marked the beginning of Amitabh Bachchan's meteoric rise as a superstar of Indian cinema. Two years later Feroz Khan’s Dharmatma (1975), inspired by the Hollywood film The Godfather, was the first ever Indian film to be shot exclusively in Afghanistan.

Throughout the 1970s the Afghan film industry continued to thrive and, on the eve of the Soviet invasion Kabul had no fewer than 18 cinemas, showing American, European, Iranian, Indian and Russian films. With the Soviet occupation came the notion of propaganda films, and a number of key film-makers left the country. An ambitious plan to create a major new film studio complex 20 kilometres from Kabul in Logar was abandoned, but Soviet trainers were brought into the country and Afghans were offered scholarships in the USSR. Noteworthy Afghan films produced during the 1980s included Paranda Mohajer (‘Migrating Birds’, 1980), directed by Engineer Abdul Latif, and Khakestar (‘Ash’, 1987), directed by Syed Worokzai.

In 1992, as Afghanistan descended into civil war, Indian director Mukul Anand came to Afghanistan to shoot a film in and around Kabul, Mazar-e-Sharif and Kandahar. Khuda Gawah (1992) starred Amitabh Bachchan as Baadshah Khan, who falls in love with Benazir, a member of a rival clan who has defeated him in a game of buzkashi.

After 1992, conflict and insecurity precluded the production of feature films, while many facilities were looted. Fortunately, staff at Afghan Film had the presence of mind to conceal more than 100,000 hours of historic footage from the National Film Archives which would otherwise have been looted or destroyed by factional fighters. In 2008 Afghan Film Director Eng Abdul Latif received on behalf of the staff of Afghan Film a Spotlight Award from the Society of American Archivists (SAA) for risking their lives to save films that chronicle Afghanistan’s rich culture and history.

Between 1996 and 2001, under the Taliban administration, moving pictures were banned and any film-making in the country was restricted to documentaries shot by visiting crews. During this period many Afghan film-makers fled to Iran or Pakistan, where some turned their hand to making videos or working for NGOs.

2001 saw the release of Kandahar, a film depicting the treatment of Afghan women under Taliban rule and directed by the Iranian Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Mostly shot in Iran, the film received attention and some critical acclaim after the attack on New York in September 2001.

Developments since 2001

In 2001, Afghan Film and the National Film Archives were re-established as part of the Ministry of Information and Culture’s Department of Film, with branch offices in Mazar-e-Sharif (Balkh), Jalalabad (Nangarhar), Kandahar and Herat; a Mobile Cinema unit was also set up to promote and screen films in the provinces. Since that time private film companies have been required to register with Afghan Film.

The National Film Archives house a rich collection of material from the past 60 years, including all films made by Afghan Film and foreign films from the Soviet Union, Iran and the region. The archives also contain a collection of 16mm films made for screening in the provinces with the Mobile Cinema unit. While much of the collection was saved during the conflict, supporting documentation was lost in some cases and efforts thus continue to re-catalogue the material. As it is housed in a building without climate control, it is anticipated that in the coming years 30 to 40 per cent of the collection may be lost to degradation. The Paris-based Institut National de l’Audiovisuel (INA) has been working with the National Film Archives to digitise the collection. Funds are also being sought for the construction of new premises which will incorporate appropriate forms of climate control.

Afghan Film chooses foreign films to be distributed and screened in 20 cinemas that have reopened, most of them in Kabul. However, all but Kabul’s Ariana Cinema - recently rebuilt with French support - remain in a poor state of repair. They screen mainly Bollywood films and formulaic Hollywood action movies, and are generally considered unsuitable for family entertainment. With the spread of television and readily-available pirate copies of movies on DVD, most Afghans now watch films at home.

Using the facilities of Radio-Television Afghanistan (RTA) for practice, the reopened Department of Cinema within Kabul University’s Faculty of Fine Arts offers a four-year Bachelor of Arts in Cinema programme. However, most production and post-production facilities in Afghanistan are thus far suitable only for video shooting. Formal training opportunities being limited, the workshops organised around the annual Kabul International Documentary and Short Film Festival and other opportunities offered by NGOs fill an important gap in the provision of training.

In recent years, principally with international support, Afghan film-makers have had an annual output of 30-40 digitally-produced short films. The shooting of full-length films on 35mm is largely restricted to returnee Afghan film-makers or foreign directors, who tend to bring their own crews and equipment in order to ensure the professional standards that are not yet common in the domestic film industry. Recruiting Afghan female actors is also a problem, leading to the employment of women from neighbouring Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

The bulk of cinematic production currently comprises low-budget action and entertainment films for domestic consumption, often incorporating Bollywood-style song and dance elements. One of the leading producers of this genre is Salimi Shahin's Qais and Shaheen Film. Among the commercial films aimed at an international audience to be shot in Afghanistan after 2001 was Rahimi International Films' epic Spring of Hope (2006), written and directed by and starring its director Hashmat Khan, an Afghan-born Indian citizen who had directed three previous Pashtu/Dari films - Sitara, Dear Afghanistan and Roya. An Indo-Afghan joint production with an all-Afghan cast and an Indian crew, Spring of Hope's post-production was completed in Mumbai. The film begins with the Russian invasion of Afghanistan and ends with the fall of the Taliban. The story follows two friends, a Tajik and a Pashtun, through their experiences in those years. It is a story of brotherhood across ethnicities and of the enduring hope for peace in their country.

Afghan art cinema came to global prominence in 2003-4 when former Afghan Film director Siddiq Barmak (b 1962) won a Golden Camera Special Mention at the 2003 Cannes Film Festival, a Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film (2004) and a plethora of other international awards and nominations for his first feature film Osama (Afghanistan/Netherlands/Japan/Ireland/Iran, 2003). Set in the Taliban era, the film recounts the story of a young girl who cuts her hair and dresses like a boy in order to get a job and support her widowed mother and grandmother. Barmak’s second feature film Opium War (Afghanistan/South Korea, 2008), a dark comedy about two American soldiers who wind up stranded in an Afghan opium field after a helicopter crash, won the Golden Marc’Aurelio Critics’ Award for Best Film at the 2008 Rome International Film Festival.

In 2004, writer, photographer and film maker Atiq Rahimi directed a film version of his best-selling book Chak o Chakestar ('Earth and Ashes’, France/Afghanistan 2004). Rahimi’s film, which presents war and its consequences as an impressive sequence of parables, makes use of montage technique, a visual structure, and an aesthetic that all derive from large-scale western cinema. It was awarded the Prix du Regard vers l'Avenir at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival.

Zolykha's Secret (Afghanistan, 2007), the first feature by Afghan documentary film maker Horace Ahmad Shansab (b 1957), has been screened widely on the international film festival circuit. It tells the harrowing story of a family struggling to eke out an existence during the last months of the Taliban regime, told through the eyes of youngest daughter Zolykha.

Recent movies directed by the prolific Engineer Abdul Latif, current Director of Afghan Film, include Farda (‘Tomorrow’, 2007) and Roshani (‘Lightness’, 2008).

Filmed primarily with non-professional actors, Barmak Akram’s debut feature L'enfant de Kaboul (known in English as Kabuli Kid, Afghanistan/France, 2008) impressed international critics for its carefully-observed details of daily life in a battered city as it follows a Kabul taxi driver in his search for the mother of a baby abandoned in the back of his cab.

In recent years several well-known Iranian film makers have shot feature films in Afghanistan, the most noteworthy being Delbaran by Abolfazl Jalili (Iran/Japan, 2001), and At Five in the Afternoon (France/Iran, 2003) and Two-Legged Horse (Iran, 2008), both by Samira Makhmalbaf, daughter of leading Iranian film director Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

Indian director Kabir Khan's debut feature film Kabul Express (India, 2006), loosely based on his and his friend Rajan Kapoor's experiences in post-Taliban Afghanistan, was banned by the government of Afghanistan on the grounds that it contained dialogue which was offensive to the Hazara ethnic group.

Capitalising on current international interest, numerous foreign films have been set in Afghanistan since the fall of the Taliban. Liz Mermin’s Beauty Academy of Kabul (USA, 2004), which follows a group of American beauticians as they travel to Afghanistan to open the country's first beauty school, proved a surprise hit at the box office.

However, perhaps the best-known Afghanistan-set foreign film of recent years is Marc Forster’s The Kite Runner (2007), based on Khaled Hosseini's best-selling novel of the same name. Set against a backdrop of tumultuous events, from the fall of the monarchy through the Soviet invasion, the mass exodus of refugees to Pakistan and the United States, and the rise of the Taliban, the film tells the story of Amir, a young boy from Kabul, who betrays his best friend.

Due to the security situation the film was shot in China’s Uyghur Province rather than in Afghanistan. It was banned by the government of Afghanistan on account of its rape scene and depiction of ethnic tensions and class struggles.

After 2001, imported Bollywood films quickly resumed their dominance of the Afghan commercial cinema market. Satish Kaushik’s Tera Naam (‘Your Name’, 2003) flopped in India but was a huge hit with audiences in Kabul, where it inspired everything from hairstyles to fashion trends. Irfan Khan's Bullet: Ek Dhamaka (2005) was another major box office success.

However, with modern Bollywood productions steadily becoming more liberal in their depiction of women and boy-girl relationships, with more suggestive scenes and songs than ever before, religious leaders have become increasingly vocal in their denunciation of Indian movies and soap operas as un-Islamic and a negative influence on Afghan society.

Upcoming film makers whose work has been featured in the past at the Kabul International Documentary and Short Film Festival include Roya Sadat (Three Dots, 2004), Dil Afruz Zeerak (A Day in the Life of Rahela, 2006), Alka Sadat (Half Value Life, 2008), Sayed Alireza Sajjadi (The Last Shout, 2008) and Abdul Rashid Azimi (The Keepsake Photo, 2009). Many of the works produced by this new generation of film-makers mirror everyday social and political struggles, focusing on issues such as forced marriage, family violence, and poverty in both rural and urban communities.

In recent years Afghanistan has also been the subject of many foreign documentary films. These have included: Afghanistan, the Lost Truth by Yassamin Maleknasr (Iran, 2003), featuring interviews of ordinary citizens a few months after the fall of Taliban; The Boy who Plays on the Buddhas of Bamiyan by Phil Grabsky (UK, 2004), about the destruction of the Buddhas; Sedika Mojadidi's Motherland Afghanistan (USA, 2006) on the rehabilitation of a hospital; Meena Nanji's View From a Grain of Sand (USA, 2006) about women’s rights; and Anwar Hajher's 16 Days in Afghanistan (Afghanistan/USA, 2007), which documents Afghans after the fall of the Taliban.

Postcards from Tora Bora (USA, 2007) by Kelly Dolak and Wazhmah Osman features personal experiences of the latter co-director; Hana Makhmalbaf’s debut film Buddha Collapsed Out of Shame (Iran, 2008) is a study of the effects of years of war on Afghan children; Ariel Nasr's Good Morning Kandahar (Canada, 2008) tells the story of a radio station; and Havana Marking’s Afghan Star (Afghanistan/UK, 2008) features four participants of ‘Afghan Star’, Tolo TV's version of ‘Pop Idol'.

Use the navigation bar on the right to make direct contact with organisations and individuals working in the film sector.