Heritage

Heritage

Historic environment

Every period of history, from the Stone Age to modern times, has left its mark in the form of archaeological features, monuments or portable objects found across Afghanistan.

A list of key sites and monuments offers a glimpse of the range and richness of the built heritage that survives in all provinces. For a brief overview of the historical context of the Greek, Indian, Persian, Central Asian, Chinese, Arab and European influences on the cultural heritage, see the overview of Afghan history.

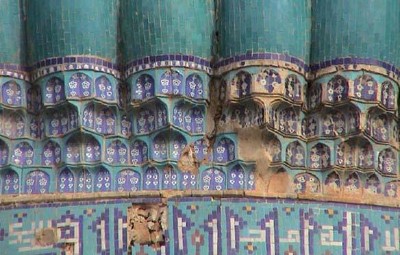

Perhaps the best-known site in Afghanistan is the Bamiyan valley, which received worldwide attention in 2001 when the two giant Buddha statues carved into the cliff in around 600 CE were badly damaged. As well as these massive figures, the valley is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as a representation of cultural and religious developments over a period of 1,300 years. Also inscribed on the World Heritage list is the 12th-century Minaret of Jam in Ghor province. In recognition of the threats facing historic monuments in the country, the 2007 World Monuments Watch List included the 9th-century Masjid-e-Noh Gumbad in Balkh, as well as the old city of Herat, which was identified in 2009 as undergoing rapid, uncontrolled ‘redevelopment’.

Perhaps the best-known site in Afghanistan is the Bamiyan valley, which received worldwide attention in 2001 when the two giant Buddha statues carved into the cliff in around 600 CE were badly damaged. As well as these massive figures, the valley is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as a representation of cultural and religious developments over a period of 1,300 years. Also inscribed on the World Heritage list is the 12th-century Minaret of Jam in Ghor province. In recognition of the threats facing historic monuments in the country, the 2007 World Monuments Watch List included the 9th-century Masjid-e-Noh Gumbad in Balkh, as well as the old city of Herat, which was identified in 2009 as undergoing rapid, uncontrolled ‘redevelopment’.With sites from the Bronze Age, through the elaborate architectural ensembles of the Gandharan civilisation - when the Classical and Buddhist traditions merged - and the fine examples of from the Ghorid and Timurid periods, Afghanistan retains an extraordinary range of built heritage, which merits further field research and scholarship. The first comprehensive gazetteer of 1,200 sites and monuments in Afghanistan, up to and including the Timurid period, was published in 1982, although the conflict has disrupted the process of updating the process of formally registering such sites or undertaking new field research.

The losses suffered during the looting of the National Museum in Kabul by factional fighters in 1993-1994 attracted major international attention. Since 2007 an exhibition of archaeological artefacts from the Tillye Tepe hoard (Hidden Treasures from the National Museum in Kabul) has travelled in Europe and the US, raising awareness as to the richness of Afghanistan’s material culture. Since 2002, the extent of illegal excavation across the country has grown to an unprecedented scale, driven by the voracious demand for objects on the international art market. A Red List of artefacts that are at particular risk was published in 2005 by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) in order to raise awareness among museum staff, dealers, collectors and customs officials.

The losses suffered during the looting of the National Museum in Kabul by factional fighters in 1993-1994 attracted major international attention. Since 2007 an exhibition of archaeological artefacts from the Tillye Tepe hoard (Hidden Treasures from the National Museum in Kabul) has travelled in Europe and the US, raising awareness as to the richness of Afghanistan’s material culture. Since 2002, the extent of illegal excavation across the country has grown to an unprecedented scale, driven by the voracious demand for objects on the international art market. A Red List of artefacts that are at particular risk was published in 2005 by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) in order to raise awareness among museum staff, dealers, collectors and customs officials.Since 2001 there have been several initiatives to return looted objects to the National Museum, most notably the collection of the Afghan Museum in Exile that was repatriated from Switzerland in 2007. More recently, 2,000 objects thought to have an Afghan provenance were intercepted by British customs and returned to Kabul.

One of the other major threats facing Afghanistan’s heritage is rapid urban growth and the associated process of ‘development’ that often results in the demolition of important historic fabric, as well as individual monuments. The absence of a coherent urban policy has resulted in ill-conceived plans and investments that risk irrevocable transformations being made on urban heritage that represent an important trace of the history of the country. Among the most dramatic transformations are taking place in the old city of Herat which, as a result of the failure of urban officials to halt illegal demolition and enforce development controls, is no longer being considered for the tentative UNESCO World Heritage List. A similar process of transformation is under way in the old city of Kabul, where recent road-widening by Kabul Municipality has driven a swathe through some important urban fabric.

One of the other major threats facing Afghanistan’s heritage is rapid urban growth and the associated process of ‘development’ that often results in the demolition of important historic fabric, as well as individual monuments. The absence of a coherent urban policy has resulted in ill-conceived plans and investments that risk irrevocable transformations being made on urban heritage that represent an important trace of the history of the country. Among the most dramatic transformations are taking place in the old city of Herat which, as a result of the failure of urban officials to halt illegal demolition and enforce development controls, is no longer being considered for the tentative UNESCO World Heritage List. A similar process of transformation is under way in the old city of Kabul, where recent road-widening by Kabul Municipality has driven a swathe through some important urban fabric.The Afghanistan National Development Strategy (ANDS) for 2007/8-2012/3, 1387-1391, identifies as key issues the compilation of a cultural heritage inventory, halting illicit traffic of cultural property, development of legal and policy frameworks for the cultural heritage sector, the conservation of historic monuments, and the improvement of cultural services.

Brief history of the National Museum, Kabul

By Joanie Meharry, with Jolyon Leslie

In around 1919, the family of Amir Habibullah Khan assembled a 'cabinet of curiosities', comprising manuscripts, medals, miniatures, weapons, and ethnographic material in the Bagh-e-Bala Pavilion in Kabul. When Amir Amanullah Khan succeeded to the throne later that year, this collection was moved to the Koti Baghcha pavilion in the precinct of the Arg-e-Kabul, and which was formally designated as the National Museum of Afghanistan. With the signature in 1922 of an agreement with France which provided for foreign archaeologists to work in Afghanistan, objects from excavations were gradually added to this collection. During unrest precipitated by the reforms pursued by Amanullah Khan, who abdicated in 1929, the Koti Baghcha was looted.

In around 1919, the family of Amir Habibullah Khan assembled a 'cabinet of curiosities', comprising manuscripts, medals, miniatures, weapons, and ethnographic material in the Bagh-e-Bala Pavilion in Kabul. When Amir Amanullah Khan succeeded to the throne later that year, this collection was moved to the Koti Baghcha pavilion in the precinct of the Arg-e-Kabul, and which was formally designated as the National Museum of Afghanistan. With the signature in 1922 of an agreement with France which provided for foreign archaeologists to work in Afghanistan, objects from excavations were gradually added to this collection. During unrest precipitated by the reforms pursued by Amanullah Khan, who abdicated in 1929, the Koti Baghcha was looted.In 1931 what was left of the collection was moved to a structure built in the 1920s to house the Municipality, in the quarter of Darulaman that was laid out by Amanullah Khan some eight kilometers south of central Kabul. Although designed as offices rather than as a museum, the structure soon had to absorb considerable quantities of archaeological material that were generated through excavations.

Under the terms of the agreement signed with the Afghan government in 1922, French teams had exclusive rights to survey and excavate in designated areas for a period of 30 years, with archaeological finds to be shared between the two countries. Not until 1952, when the agreement with France was renewed, were provisions made for other archaeological missions to work in Afghanistan. This led over time to the involvement of archaeologists and other specialists from Britain, India, Italy, Japan, the USA and the USSR. In 1964, it became official Afghan government policy that all finds in the country would remain the property of Afghanistan, and two years later the Afghan Institute of Archaeology was established.

Under the terms of the agreement signed with the Afghan government in 1922, French teams had exclusive rights to survey and excavate in designated areas for a period of 30 years, with archaeological finds to be shared between the two countries. Not until 1952, when the agreement with France was renewed, were provisions made for other archaeological missions to work in Afghanistan. This led over time to the involvement of archaeologists and other specialists from Britain, India, Italy, Japan, the USA and the USSR. In 1964, it became official Afghan government policy that all finds in the country would remain the property of Afghanistan, and two years later the Afghan Institute of Archaeology was established.From its modest beginnings as a collection of objects of interest to the royal family, the National Museum was transformed by the artifacts obtained during excavations after the 1920s. Not only was there a considerable amount of material from the Kushan site at Hadda, but also the Greek site of Ai Khanoum, the Bronze Age site of Mundigak, the Buddhist site at Bamiyan, as well as Begram, Surkh Kotal, Paitava and Shotorak, all of which shed light on Afghanistan’s rich history. The reputation of the National Museum grew as material from the collection was exhibited abroad during the 1960s.

It was, however, not until 1978-1979 that an important horde of gold objects was excavated by a Soviet team at nomadic graves in Tilla Tepe, Jowzjan Province. On the eve of the Soviet invasion, this material was transported to the National Museum for cataloguing and storage. By this stage, the museum reportedly had more than 100,000 artefacts in its collection. With the unrest associated with the Saur revolution in April 1978, however, work was disrupted and the museum building was occupied by the Ministry of Defence, who occupied the wider Darulaman quarter. The collection was packed and transported into storage into the city centre until 1980.

It was, however, not until 1978-1979 that an important horde of gold objects was excavated by a Soviet team at nomadic graves in Tilla Tepe, Jowzjan Province. On the eve of the Soviet invasion, this material was transported to the National Museum for cataloguing and storage. By this stage, the museum reportedly had more than 100,000 artefacts in its collection. With the unrest associated with the Saur revolution in April 1978, however, work was disrupted and the museum building was occupied by the Ministry of Defence, who occupied the wider Darulaman quarter. The collection was packed and transported into storage into the city centre until 1980.Even after the return of the collection to Darulaman, the political instability had an impact on the operation of the museum. Despite the fact that all international archaeological teams forced to leave the country as the conflict spread, staff of the museum continued to work on cataloguing finds and creating new displays of finds from Ai Khanoum, Delbarjin wall paintings, and a Hindu Shahi marble Surya discovered in Kabul's Khairkhana district. In response to fears for its safety, the Tillya Tepe horde was transported in 1985 to the Koti Baghcha and only returned to Darulaman in 1988. In 1989, the museum was formally closed and the bulk of the collection dispersed to safer sites closer to the city, with the most valuable items stored in the vaults of the Central Bank.

With the abdication of Dr Najibullah in 1992, fighting soon broke out between the mujahideen factions who had occupied Kabul. Having been used since the 1970s by the Soviet-backed Ministry of Defence, the Darulaman Palace took on symbolic importance, and the adjoining National Museum stood perilously close to the front-lines between fighters of Hizbe Wahdat and Hizbe Islami. In May 1993 the building was set alight, destroying the roof and the most of the upstairs displays. This paved the way for Hazara fighters from Hizbe Wahdat to loot the premises at will, over a period of some weeks. Having been informed of this and negotiated access to inspect the site, UN staff made efforts to safeguard the surviving objects in the stores, while formally urging the leader of Hizbe Islami, Ustad Mazari, to restrain his fighters. This proved to be in vain, however, as the looting continued until there was very little of obvious worth that could be carried from the premises. After the fighting had abated, some of the surviving portable objects were transported by UN staff to the city centre, while steel doors were installed on the remaining stores and the ruined upper floor of the building was weatherproofed.

With the abdication of Dr Najibullah in 1992, fighting soon broke out between the mujahideen factions who had occupied Kabul. Having been used since the 1970s by the Soviet-backed Ministry of Defence, the Darulaman Palace took on symbolic importance, and the adjoining National Museum stood perilously close to the front-lines between fighters of Hizbe Wahdat and Hizbe Islami. In May 1993 the building was set alight, destroying the roof and the most of the upstairs displays. This paved the way for Hazara fighters from Hizbe Wahdat to loot the premises at will, over a period of some weeks. Having been informed of this and negotiated access to inspect the site, UN staff made efforts to safeguard the surviving objects in the stores, while formally urging the leader of Hizbe Islami, Ustad Mazari, to restrain his fighters. This proved to be in vain, however, as the looting continued until there was very little of obvious worth that could be carried from the premises. After the fighting had abated, some of the surviving portable objects were transported by UN staff to the city centre, while steel doors were installed on the remaining stores and the ruined upper floor of the building was weatherproofed.It was partly in response to the appearance of looted items from the collection of the National Museum on local and international markets, that in late 1994 a group of concerned individuals established the Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan’s Cultural Heritage (SPACH) with the goal of drawing attention to the plight of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage. In 1995, a delegation from the Musée Guimet began to assist staff from the National Museum in inventorying what had survived from the museum collection, which remained in storage in central Kabul.

Given the international outcry that resulted from coverage of the looting of the museum, the administration in Kabul, then led by Burhanuddin Rabbani, issued a number of radio appeals for objects to be returned. The Kabul Hotel was designated as a temporary home for what remained of the collection, which was catalogued and packed by museum staff, working in very difficult conditions.

Given the international outcry that resulted from coverage of the looting of the museum, the administration in Kabul, then led by Burhanuddin Rabbani, issued a number of radio appeals for objects to be returned. The Kabul Hotel was designated as a temporary home for what remained of the collection, which was catalogued and packed by museum staff, working in very difficult conditions.With the establishment in 1996 of a Taliban administration in Kabul, security improved markedly and museum staff were able to continue work on the inventorying. With the completion in July 1998 of repairs to the ground floor of the war-damaged museum, material that had been transported to the Kabul Hotel were moved to the nearby premises of the Ministry of Information and Culture.

In July 1999, the Taliban leader Mullah Omar issued two decrees, ‘Concerning Protection of Cultural Heritage’ and ‘Concerning Preservation of Historic Relics in Afghanistan,’ which aimed to safeguard cultural sites and objects, while limiting illegal excavations. In August 2000, the National Museum mounted an exhibition of the recently-discovered Rabatak inscription. By the end of the year, the museum’s inventory listed some 7,000 objects or object pieces from more than 50 sites.

Following a decree issued in February 2001 by Mullah Omar to destroy figurative statues, on the grounds that they once served as idols for non-believers, the Bamiyan Buddhas were badly damaged by Taliban fighters. Not long after this, Taliban officials were sent to destroy statues from the collection, both in the National Museum and in the stores at the Ministry of Information and Culture. This resulted in serious damage to schist, plaster and wooden figures – although many objects were saved from destruction by museum staff, who had hidden them out of sight of the zealous Talibs assigned to this task.

Following a decree issued in February 2001 by Mullah Omar to destroy figurative statues, on the grounds that they once served as idols for non-believers, the Bamiyan Buddhas were badly damaged by Taliban fighters. Not long after this, Taliban officials were sent to destroy statues from the collection, both in the National Museum and in the stores at the Ministry of Information and Culture. This resulted in serious damage to schist, plaster and wooden figures – although many objects were saved from destruction by museum staff, who had hidden them out of sight of the zealous Talibs assigned to this task.Since 2002, a number of initiatives have been taken to reconstruct the physical fabric of the museum and to recover and conserve the surviving collection, mainly with support from Italy, France and Greece. By early 2007, inventories of eight collections and the preparation of a database had been completed, in parallel with three programmes of conservation, including some of the schist objects damaged by the Taliban. In addition, training was provided to museum staff in collections management, photography, IT and language. Since then, there have been a number of small exhibitions in the newly-restored premises, although only a tiny fraction of the collection has been displayed. Following the ‘rediscovery’ in the vaults of the Central Bank in 2006 of the Bactrian gold horde from Tillya Tepe, along with many other objects, these have been the focus of a travelling exhibition entitled Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul, which has already toured Europe and North America and will travel on to east Asia in 2012. In March 2011 the Embassy of the United States of America in Afghanistan and the Ministry of Information and Culture pledged funds for a new museum building with state of the art security, conservation and administrative space as well as exhibition space for the material shown in the travelling exhibition. Further US funds were pledged for training and capacity building for the National Museum staff.

Further reading

Warwick Ball, The Monuments of Afghanistan. History, Archaeology and Architecture (London 2008).

Warwick Ball, Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan (Paris 1982).

Jolyon Leslie, Culture and Conflict in the Future of Afghanistan (Washington DC 2009).

Heather Bleaney and María Ángeles Gallego, 'Afghanistan: A Bibliography', in Handbook of Oriental Studies 13 (2006).